The EBRD’s Innovation Programme in Lebanon, funded by the European Union, is playing a vital role bridging the longstanding gap between industry and academia. Launched three years ago at a time when collaboration between the two spheres had long been seen as difficult, the programme is giving startups and SMEs access to researchers, R&D institutions and specialised consultants through grants and tailored advisory services designed to advance innovation-driven projects.

By providing a structured path for partnership, the programme is helping Lebanese businesses tap into academic expertise and drive their innovations forward.

The EBRD and the Lebanese American University Industrial Hub (LAUIH)

Around the same time that the EBRD was launching its Innovation Programme, the Lebanese American University launched its Industrial Hub – a dedicated research facility born of the same diagnosis: academia and industry were working in silos, while universities themselves were struggling to sustain research units under the weight of the economic crisis and currency devaluation.

At the time, the LAUIH was created as a means to diversify streams of income in order to preserve the university’s research capabilities, by opening its labs and expertise to the private sector. Today, the hub offers a wide spectrum of services: everything from rapid consultancy to full machine design and development, turnkey engineering solutions, and software builds. The initiative also emphasises students’ experiential learning, giving local and international companies direct access to university talent, and students hands-on experience through tailored training and paid internships.

But rebuilding the trust between Lebanese industry and academia was not straightforward, as Dr Ali Ammouri, Director of the LAUIH, explains: "I was navigating how to get businesses to work with us and help them grasp that the world of academia can actually deliver real and practical solutions. That’s where the EBRD’s Innovation Programme changed everything."

By offering grants and co-financing the research journey, the programme lowered the barrier for companies to engage with the LAUIH and benefit from research, consultancy and product development, including the contribution of young university talent. For many, it is the first time they have had access to this level of innovation capability.

Up to now, the LAUIH has collaborated with the EBRD on more than 30 projects, one of them with the pioneering biotech startup DLOC Biosystems.

A scientific breakthrough

Some of the most groundbreaking ventures owe their success to entrepreneurs with a multidisciplinary approach. Wadah Maleb is a case in point: a mechanical engineer, he discovered a new interest in biomedical science while participating in a breast cancer research project and studying the physiology of breast ducts. He grew frustrated that most preclinical experiments, although promising, failed to translate into clinical trials.

"The problem was deeper than that," Wadah explains. "We grow cells randomly in 2D, while human physiology is vastly more complicated. Nothing we grew in the lab accurately mimicked what happens in the human body."

So he put on his engineering hat and began searching for models that could recreate human-like tissue environments and offer better predictions of how drugs behave in the body. That search led him to organ-on-chip technology which, although not entirely new, "didn’t grow tissues in an accurate way," he says.

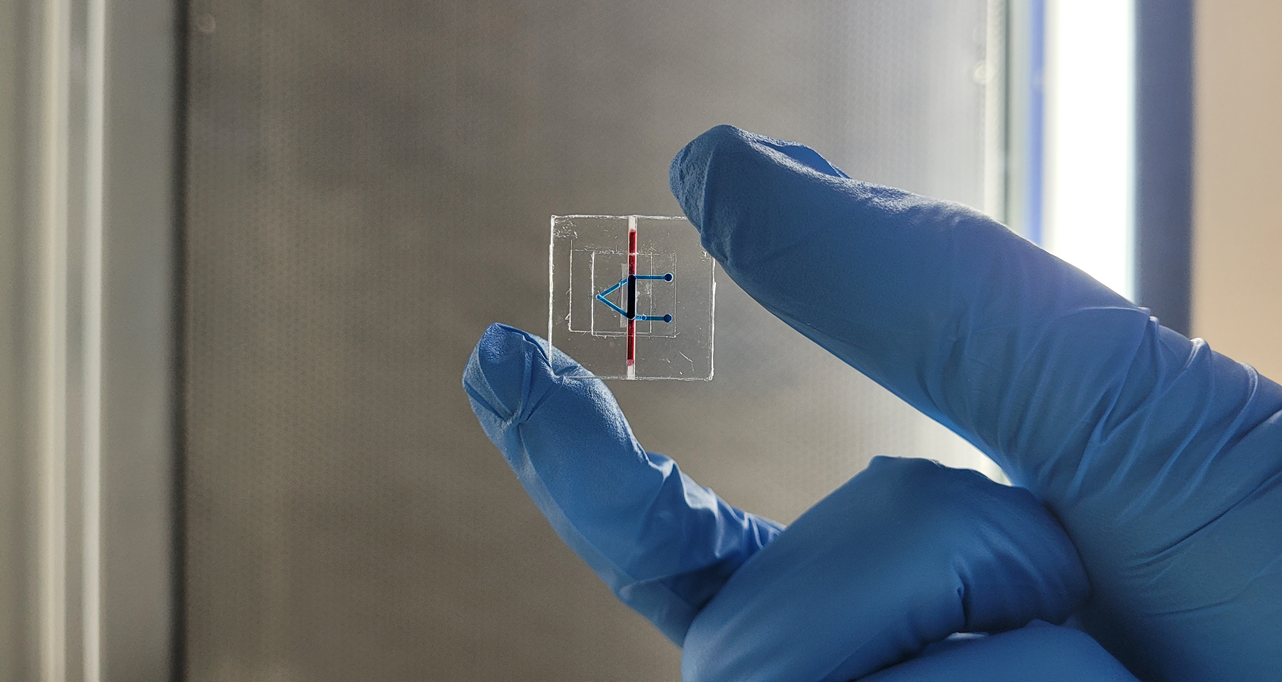

Wadah developed his first biochip simulation into his Master’s thesis: an early conceptual model containing microscale scaffolds where cells attach to engineered surfaces to form 3D tissues resembling those in the human body. But when it came to actually manufacturing the chip, he hit a brick wall, lacking the funds and technology to engineer the micro-scaffolds he had designed.

Wadah went on to secure funding by winning multiple local and international entrepreneurship competitions, including Qatar’s Stars of Science innovation programme, where he refined early manufacturing methods and demonstrated feasibility of the technology. But even with these wins, scaling the prototype to a functional, test-ready system remained prohibitively expensive, whereas he had raised just $500,000 (€430,000) to initiate the company’s earliest R&D activities.

The solution, he realised, lay in education and resourcefulness.

Bridging the funding gap

He approached the faculty of medicine at the American University of Beirut (AUB) to help him evaluate and refine early prototypes according to biological requirements. He invested the funds he had into developing the machines needed for the initial manufacturing steps, while manually performing the remaining specialised tasks to avoid premature large-scale automation costs. He needed dentists, technicians and even artists with engraving skills to assist with those tasks. Eventually he found an artist dexterous enough to engrave on a grain of rice. The bar for precision was so high that, out of 1,000 assembled chips, having even one functional chip was regarded as a success. These experiments generated essential engineering data that later formed the basis for automating the entire manufacturing pipeline at a fraction of the expected cost.

This funding enabled Wadah to support the company’s earliest stages: proof of concept, technological development, a small initial team and, eventually, a modest lab. These efforts laid the foundation for what would become DLOC Biosystems.

One of the team’s biggest challenges was operating across multiple layers of the technology at once. The entire mechanism behind producing their chips is unique. No off-the-shelf machine could be bought to do the job; instead, they had to design and build their own tools to execute each step of chip fabrication.

Once they had identified the precise parameters needed for chip manufacturing, they began transforming the formerly manual process into a semi- and eventually fully-automated workflow. In 2023, Wadah applied for the EBRD’s EU-funded Innovation Programme in Lebanon, which connected him with the LAUIH. The hub’s support allowed him and his team to automate key steps efficiently, optimise operations, and build robust systems while maintaining full ownership and internal control over their intellectual property.

"This programme created a bridge," says Wadah. "It gave us the chance to improve operations with experts at the LAUIH and advance our product faster than we could have alone."

DLOC Biosystems’ new biochip could now model a single tissue or organ in the lab, but that alone is insufficient. "The human body doesn’t operate in a static microenvironment," Wadah reminds us. "Organs are connected, and each contains multiple cell types and relies on constant flows of blood and fluids."

Reaping the rewards of collaboration

From that point onwards, DLOC Biosystems’ took organ-on-chip technology in a whole new direction, pioneering a human-on-chip platform that integrates multiple organ models with real-time measurement.

The challenges are immense but worthwhile, as Wadah expands: "We can’t just model or grow cells randomly in 3D. We need to grow them exactly as they form in the human body with the same structures, the same complexity. Our goal is to recreate these tissues with real accuracy to facilitate drug development and make it less costly. That’s why we didn’t stop at simply making a chip."

Today, DLOC Biosystems has grown to a team of more than 20, with patents filed and strong angel investment behind it. While there are many potential avenues for business development, the company is now focusing on offering its services for preclinical drug testing to pharmaceutical firms and research organisations.

Building on his collaboration with the LAUIH, Wadah is seeking new partners to design additional organ models, develop better alternatives to traditional drug testing, and grow revenue. DLOC Biosystems’ ultimate goal is to reduce the massive cost and time needed to develop a drug (often exceeding $2 billion (€1.7 billion) and 12 years) by scaling and commercialising its human-on-chip technology through upcoming Pre-Series A and Series A investment rounds.

The venture is a shining example of the EBRD’s facilitation of academia helping to realise industrial goals and looks set to yield advances in healthcare and commercial success.

Select an image to expand

Select an image to expand